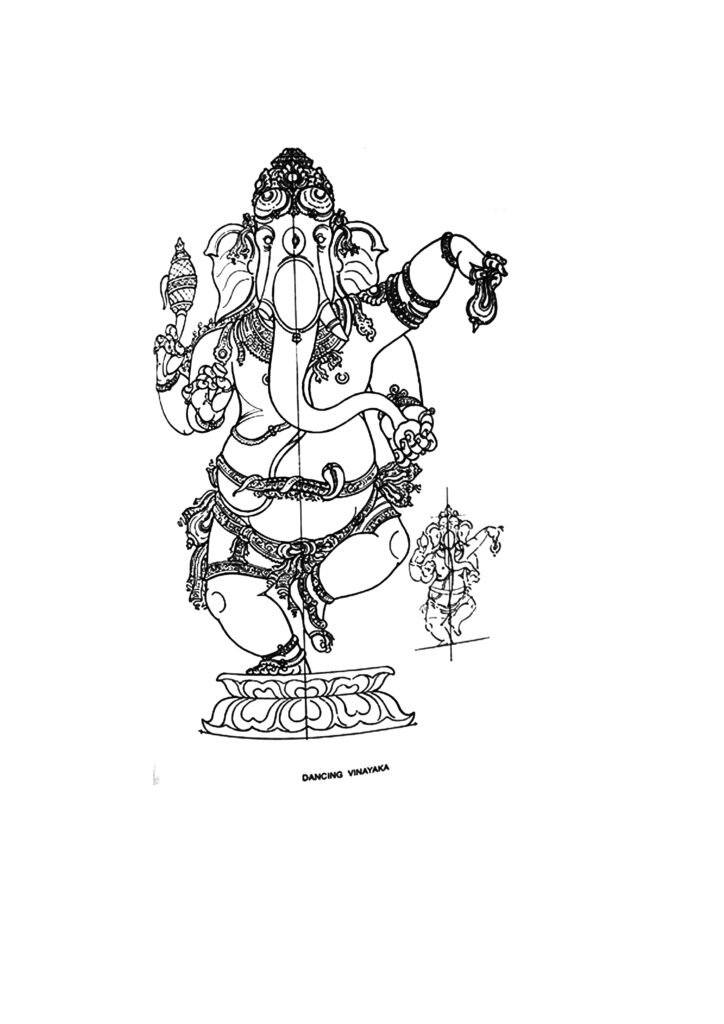

Article By: Ar. Sashikala Ananth

Ganesha Sketch credit: Indian sculpture & Iconography by Ganapathi Sthapathi & translated by Sashikala

Ananth

(Sanskrit- PrathimamAnAlakshanam Tamil- Shilpa chenul)

In the field of vAstu shilpa shAstra the importance given to ratios and proportions is very high. Let us look at the place of tAla in all the traditions to understand it.

tAla: it’s a name given to rhythms in sound that is also known as tempo. In the visual field, it is called mukham, tAla, pada, or module. In Indian classical music, tAla plays a pivotal role. It is both an audible rhythm maintained by the skin drums such as mridanga, tabla, etc and the inherent rhythm maintained by the musician with the hands. In dance, the tAla is maintained by the feet. Through sustained and intense practice the tAla becomes a part of the body, voice, and emotions of the artist. Therefore even if there is no drum playing, the musician or dancer will not miss a beat.

In the same way, Vedic chanting also holds a very powerful rhythmic structure that is internalised by the person who is chanting. Here the tAla and the shabda or sound merge to create a complete pattern. This tAla is part of what is called Chandas and also takes years of practice to get internalised and embodied by the person.

What is important to pay attention here is that in every one of these traditions, there is a methodology to learn and manifest this structure. It takes years of sAdhanA. For the total impact of this sound on the Rasika or listener/viewer the artist and the vaidika have to offer it with sincerity and precision. The body and the voice have to be carefully prepared to transfer this rhythm into the space. It is said that when the artist offers from a deep and quiet inner space, this manifestation is capable of transforming the listener/viewer.

shishurvEtti pashurvEtti vEtti gAnarasam phaNiH

“This chanting or singing that comes from a meditative space and has its root in the Vedas is capable of being understood by animals, babies and snakes”.

tAla in vAstu shilpa:

vastu is the form and vAstu is the space in which the smaller form exists. Therefore, the relationship between form and space is the essence of vAstu shAstra. When a form or vastu that inhabits a space is out of alignment then there is a disturbance in the inner alignment of people who occupy the space. Every individual component in the space has to be in rhythmic balance with each other and with the overall space. This lakshaNa takes years of disciplined practice to manifest in the physical space. Such a sAdhana when it manifests, is what we call tAla, pada and samyama.

Proportions are a mathematical algorithm that is extended to every aspect of the built form. Once a module has been chosen, it’s multiples and fractions are used to create all the elements of the form.

For example: if the width of a module in a paramasayika pada gruha ( a grid of 9×9) is 5′ after calculating for shaDAyAdi poruttam (auspicious measurement), then the total width can be 5 times 5′ ie. 25′;

The length can be 9 times 5′ ie 45′;

The size of rooms can be 2,3,4 times the size of the module;

The doors can be 3/4 module wide and 1 1/2 modules high;

The size of columns in the veranda can be 1/5 of the module;

The height of the rooms can be 2 times the module when they are small, and 2 1/2 times when they are larger rooms.

The entire building can be 3,4,5 times the module in height and so on.

The interplay of the ratios and proportions cannot be random, it must fall into the 3 principles of design: bhogaDyam, sukhadarshanan and ramya.

bhogaDyam refers to the usefulness of the element, sukhadarshanam refers to the aesthetics of the element and the integration of the elements in the larger form (not unlike the place of swaras in a rAga. when the balance is not correct the rAga loses its integrity). ramya stands for the choice of the rhythm, the tAla, the numerical value and the frequency of the energy that permeates the built form.

This process is very subtle/sukshma and has to be learnt under an able Guru.

Anoop is a student of Yoga, an entrepreneur, a coach and a father of two young boys. He has led successful leadership stints in both the corporate and non-for-profit sectors. On encountering the country’s water/farmer crises at close quarters, he decided to pause and examine the impact various ‘isms’ – capitalism, colonialism, etc., were having on us as individuals, families, the society and the environment at large. This quest led him to formally engage with traditional Indic knowledge systems while also learning from the latest advances in science – about our physical and mental wellbeing, importance of body and mind work in healing trauma and the urgent need for a conscious rebuilding of family / work / social structures if we have to thrive individually and collectively. Insights, frameworks and processes gleaned from these on-going studies, an anchorage in his own personal practice and his wide-ranging experiences is what Anoop brings to facilitation/coaching spaces in Ritambhara and his various professional engagements.

Anoop is a student of Yoga, an entrepreneur, a coach and a father of two young boys. He has led successful leadership stints in both the corporate and non-for-profit sectors. On encountering the country’s water/farmer crises at close quarters, he decided to pause and examine the impact various ‘isms’ – capitalism, colonialism, etc., were having on us as individuals, families, the society and the environment at large. This quest led him to formally engage with traditional Indic knowledge systems while also learning from the latest advances in science – about our physical and mental wellbeing, importance of body and mind work in healing trauma and the urgent need for a conscious rebuilding of family / work / social structures if we have to thrive individually and collectively. Insights, frameworks and processes gleaned from these on-going studies, an anchorage in his own personal practice and his wide-ranging experiences is what Anoop brings to facilitation/coaching spaces in Ritambhara and his various professional engagements.

Priya is a Yoga therapist in the Krishnamacharya tradition. She adapts Reiki & energy work, Vedic chanting, life coaching & Ayurvedic practices in her healing spaces. She is committed to nurturing collectives that have the praxis of Yoga at their heart.

Priya is a Yoga therapist in the Krishnamacharya tradition. She adapts Reiki & energy work, Vedic chanting, life coaching & Ayurvedic practices in her healing spaces. She is committed to nurturing collectives that have the praxis of Yoga at their heart. Anisha has been on an exploration to understand herself through yoga for the last 15years which led her to teaching yoga, yoga therapy and inner work through yoga.

Anisha has been on an exploration to understand herself through yoga for the last 15years which led her to teaching yoga, yoga therapy and inner work through yoga. Apoorva chanced upon Yoga in her early 20s. A spark was lit within and there was no turning back. Her exploration led her to the Krishnamacharya tradition more than a decade ago. Curious about human behaviour and what drives it, she was thrilled when her search ended (and also began) when she first came upon the Yoga Sutra, which illuminated a path towards answering many questions that had been held for a long time.

Apoorva chanced upon Yoga in her early 20s. A spark was lit within and there was no turning back. Her exploration led her to the Krishnamacharya tradition more than a decade ago. Curious about human behaviour and what drives it, she was thrilled when her search ended (and also began) when she first came upon the Yoga Sutra, which illuminated a path towards answering many questions that had been held for a long time. Anita is a yoga teacher and therapist in the tradition of Sri.T.Krishnamacarya and Sri T.K.V. Desikachar, a Reiki practitioner and a Life Coach. She is also the founder of Vishoka, a center for learning Indic and energy-based frameworks for living and healing. Her deep concern for human suffering and the problems of unsustainable living kept her on the path of seeking an integrated approach to looking at life, living, learning and healing.

Anita is a yoga teacher and therapist in the tradition of Sri.T.Krishnamacarya and Sri T.K.V. Desikachar, a Reiki practitioner and a Life Coach. She is also the founder of Vishoka, a center for learning Indic and energy-based frameworks for living and healing. Her deep concern for human suffering and the problems of unsustainable living kept her on the path of seeking an integrated approach to looking at life, living, learning and healing. Ankit is a seeker in the wisdom traditions of India. The core of his work includes creating dialogic spaces where people can look within and see the connection between their inner and outer lives. Inspired by the likes of Gandhi, Aurobindo, Vivekananda and Guru Gobind his experiments in service took him back to his roots in Punjab where he is creating a community-led model of higher education which is open, inclusive and accessible for all. Ritambhara for him is a space for engaging in a community which is committed to a DHramic life. He anchors his work of learning and leadership in the Antaranga Yoga Sadhana and the humanistic wisdom of Mahabharata.

Ankit is a seeker in the wisdom traditions of India. The core of his work includes creating dialogic spaces where people can look within and see the connection between their inner and outer lives. Inspired by the likes of Gandhi, Aurobindo, Vivekananda and Guru Gobind his experiments in service took him back to his roots in Punjab where he is creating a community-led model of higher education which is open, inclusive and accessible for all. Ritambhara for him is a space for engaging in a community which is committed to a DHramic life. He anchors his work of learning and leadership in the Antaranga Yoga Sadhana and the humanistic wisdom of Mahabharata.