I met Raghu in 2009, at a lab called Learning Theatre. I was 25, and although to many people I might have seemed perfectly normal, deep down inside I couldn’t shake the feeling that something was wrong. Truth be told, I was lost. I didn’t know where I was going, I only knew that I couldn’t stay where I was.

Learning Theatre was a watershed moment for me; for the first time in my life, people spoke about meaning and purpose without attributing it to social constructs of career and marriage. We delved deep into our personas and our past experiences. We found the courage and the safety to examine the wounds we had been carrying so far, and allow a healing to begin.

This lab, that Raghu facilitated, opened my eyes to myself, the person I was and the person I was inadvertently becoming. I took a leap of faith, and that set me off on a journey of self discovery that is still continuing today.

Fast forward almost 10 years later, and I find myself at Ritambhara Ashram, a yoga and meditation centre deep in the Nilgiris. It is a haven, a place where you can draw in deep, clear breaths of air and let go of tensions you never even knew you carried. Ritambhara Ashram is a centre for learning and transformation, built by Sashi and Raghu, created out of decades of fostering and nurturing the spirit of self transformation within themselves and others like me. Where does such a place come from? How and when did they begin this journey?

I chose to speak with Raghu and Sashi separately, to hear their individual stories and learn how they came to create this sacred space to share with the world.

Raghu: I guess it started a long time back. Now that I’m 67, I have the opportunity to really look back, and the turning point for both Sashi and myself, was when we met Dharampal. Our meeting made sense, because we were already searching. We were questioning the systems around us, the status quo, asking ourselves what kind of life we wanted to live.

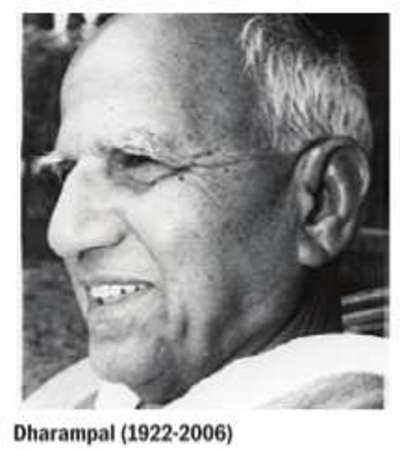

Dharampal, as I come to learn, was a pivotal figure in Raghu and Sashi’s lives. A Gandhian thinker, he was instrumental in revealing the true nature of India’s social, political, scientific and cultural achievements before the British conquest. Raghu met him while completing his degree in mechanical engineering at IIT. But I want to go back further; I’m interested to see who Raghu was as a child.

Anjali: You often speak of yourself as being a privileged person, yet you chose to work with yoga and in the developmental sector. What kind of family did you grow up in? What was the place you came from that made you ask these important questions?

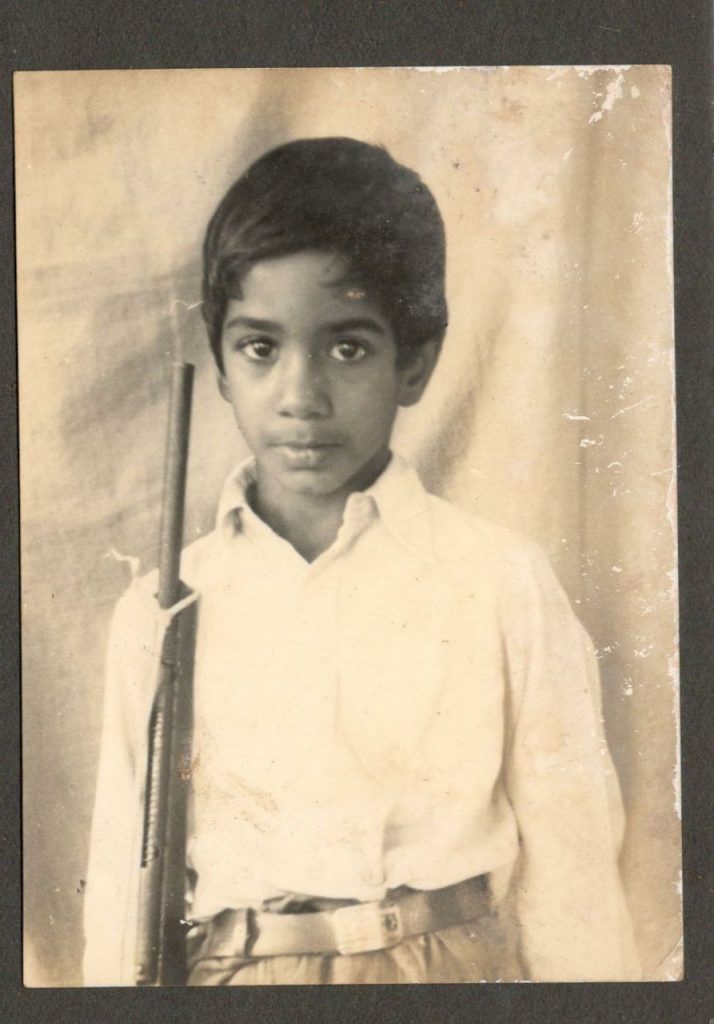

Raghu: I don’t know if there was anything special in the family that made me ask these questions; I think I was always asking them, which didn’t make me very popular at home or school.

I remember when I was about 12 or 13, I had to undergo the Uppanayanam ceremony. I asked my family what this was all about and why it had to be done. It was the usual scene, amusement and laughter at this little fellow who was asking such questions. When I persisted, they would say, “We’ll tell you later.” So I went through with the ceremony, and made a decision. I would do all the prayers for a year, during which time I would continue to ask for the meaning of the rituals and prayers. If, at the end of that year, I couldn’t find out exactly why I was doing this, I would stop. I kept asking people, even uncles of mine, who were supposed to be wizards in Sanskrit and claimed to understand the scriptures, but none of them could give me a clear answer. At the end of that year, I gave it up completely. Only later on, once I discovered the meaning for myself, did I continue the practice.

There were lots of little things like that, now that you’re asking. While at school, in Don Bosco, our principal, Father Mallon, a 6 foot 3 inch Irishman, would stand at the school gate to make sure there were no truants. One day I was heading out and he asked me where I was going. I replied that I was going home because there was a religious festival I had to attend. He said, “Oh, you’re going to pray to your monkey gods, is it?”

I turned around and said, “You’re no one to speak to me like that, Father.” I got whipped for it the very next day. I must have been in 4th class then.

Anjali: I’ve never had to deal with that kind of contempt for my religion or heritage. Was it very common during that time?

Raghu: Oh, it still exists, but I suppose it was more pronounced back then. And of course, there’s a history to it, which you learn when you read Dharampal.

Anjali: You went to college at IIT, Madras, during which time you met Dharampal. What was the climate of India at that time, what were the kind of conversations amongst people of your generation?

Raghu: Some of the conversations that were happening were around Nehru and his decisions for the future of India. He had just passed away, and there was a disenchantment with his policies. Worldwide, there were questions concerning government and social movements – we had the Vietnam war and protest music.

There was a very close friend of mine who actually left IIT and joined the Naxal movement. Quite a radical decision, so you can imagine before that, for three years, there was a lot of conversation concerning what was happening in India, in the countryside.

On a personal note, college was ending, and one had to make up one’s mind, what was one going to do? There were two options for us at that time. Stay in India, or go abroad.

Now, the only way one could go abroad, which is almost the same case today, was to get a scholarship working with a privately funded or NASA funded body. And given the state of affairs, the question was “Do you want to join a place where you will put your effort into making things that will definitely be used for war?”

Then again, if I stay in India, what opportunities are there for me?

Anjali: How did you come to make that decision?

Raghu: I had a professor called Dr. CV Seshadri. He posed a question to us students, “How can you use science and technology to solve the simple problems of regular people?” He was a really fabulous thinker, and he said “This is the way to go. I’m a scientist, I am from IIT, I can solve a simple problem.” For example, he built a beautiful catamaran which was lighter and much more efficient that the normal ones, using large, lightweight, plastic pipes. Just one example.

You know, the reason why an IIT or a School of Architecture was set up, was so that we would gain expertise and come and work for India. If you look at it, we were paying a pittance for our education at that time. So the question begs to be answered, “Why is the country investing in you?” There were a hell of a lot of opportunities for you to use your knowledge, but at that time people thought that there weren’t any opportunities to make money.

Dharampal used to ask us two, very important questions.

“Can we become a great nation by running behind the tails of the West? Can you lobotomise your brain to make it Western?”

They are both, very profound questions.

Let’s take the first. Can we become a great nation by running behind the tails of the West? The answer is quite obviously, no.

Anjali: A lot of people would think that the West is to be emulated.

Raghu: You can emulate it, yes. There are things you can learn, but learning from someone is not the same as running behind their tail. If you’re constantly running behind someone, following their fads and fancies, you will only end up an imitator.

The second question is extremely simple yet equally profound. Granted that India is a lousy nation, and all of us Indians, who have grown up being Indian, are lousy because we are Indian, can you lobotomise your brain to make it Western?

You can’t, you will always be Indian.

So what do you do?

You start to look around at where you are, you start to investigate as to how you got here. Instead of repeating the statement that India doesn’t give us any opportunities, you start to look at the opportunities that are there. Instead of saying India doesn’t have any science and technology, you start to read and discover the truth.

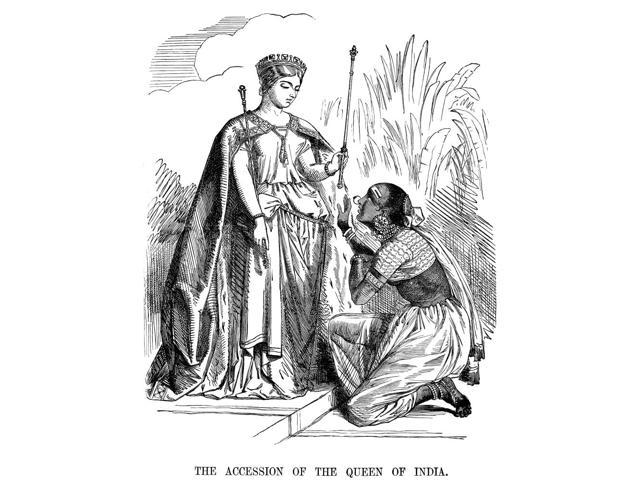

When you look into the work that Dharampal Ji had done, regarding the condition of India around the time the British conquest took place, you come across huge depths of thinking, of sciences of metallurgy, mathematics etc. We governed ourselves, we were an extremely rich nation. And in the context of that time, many of the answers that were available from our own history were much more meaningful than what you were reading or getting from the West. What was coming from the West was a colonised idea of the world. And why did we have this idea?

Like I said earlier, there’s a history to this. At the time of Independence, Nehru decides that if Indians don’t have a Westernised education, they will not have a scientific temperament. So he worked on the education policy in such a way that foreign missionaries would be invited into India to teach.

He believed that if you had an education similar to Dayanand Saraswati and other such people, then you wouldn’t have a scientific temperament. That’s because everything he knew about India came through the Western frameworks that were being used to look at India. This goes quite deep.

Nowadays, you have people like Sashi Tharoor becoming very popular with his Britain bashing. Dharampal spoke about this years ago, with very few people caring to listen. These were the fights that were actually going on at that time, and you still had people who had lived at the time of Independence and whose voices were still alive.

Anjali: You and Sashi, by virtue of being part of the youth at that moment in time, could be considered as falling into the Woodstock Generation. You’ve spoken about your friend who became a Naxalite, and protest music. What were the thoughts and feelings of your generation?

Raghu: If I go back, I think there were 3 kinds of people of my generation, and I’m obviously simplifying here.

There was one set of people whose idea of the world came from TIME and Life Magazine. The whole point was to understand America, be abreast of whatever was happening abroad and they had very little understanding of India. They wouldn’t care to have a long discussion with anyone who believed otherwise. They believed one hundred percent that if India was backward it was because we were Indian.

Anjali: What does that mean?

Raghu: Most of us have been educated using frameworks of history that were written for and by the British, which they just followed. Badly written history. Typically, even now, if you take a history book, there is very little about a Chola dynasty, which lived for much longer and had many great accomplishments, or a Vijaynagar empire. Even Ashoka – history books touch upon the wars that he fought, but rarely upon the social changes he brought about, and even that is not dealt with any degree of respect. Whereas the amount of history that you studied on the Mughal period or the British period is huge compared to an understanding of the Indian continuity.

So there were a lot of people who had no idea of India and therefore their view of India was very coloured by Western interpretations of what India was. Simply put, you were backward because you were a backward people.

Whatever concessions were given to India, whatever greatness was attributed to India, was for some strange, spiritual past, with the caveat that this spiritual past was basically useless, it wasn’t pragmatic or scientific. Yes, you have the Vedas, but it’s some arcane spiritual mumbo jumbo.

Later, though, when I got to studying the Vedas, a lot of them talk about metallurgy and mathematics. But few people bothered to find out what was actually written in the Vedas and they simply mouthed interpretations from somebody who came from the West.

I must have looked confused at this point, because Raghu smiles and elaborates.

We don’t have to study ourselves, we know who we are right? It’s the other person who has to study you. The British studied us so that they could defeat us. If I go and use those same frameworks of interpretation and understanding of myself and my culture, what I will get is a distorted picture. Unfortunately, most of the history that we have been taught is like that, very one-sided.

He picks up the thread again.

So, you have one set of people who are “educated and modern”, saying, “IIT is the gateway to a glorious future, glorious future equals going to America.”

You have another set of people who were steeped in the Indian context and culture. Very Indian, and to be looked down upon. In IIT, for example, somebody who liked Carnatic music, or who wore a dhoti to college, would be called a Lungi. That’s meant to be derogatory.

Then there were a few of us who straddled both worlds. For example I would be seen at Carnatic music concerts and I would be singing Dylan songs. So the “Lungis”, when they saw me, would say, “Hey, what are you doing here?” and the Woodstock fellows would say, “Hey, why are you going there?” It was ridiculous. One of us was a concert level musician, a violinist and a flautist, but the heroes were the ones singing Dylan and Crosby, Stills&Nash. As though wearing jeans made you superior to someone who wore a dhoti.

And then, there was this whole cross section of people who were very simple, honest, normal folk. The kind who just take whatever is told to them by the politician, by a Nehru or a Gandhi, or whichever important figure happens to be there. And India has a lot of these people; simple honest folk who have tremendous traditional understanding. When you speak with them, their understanding of the soil, of philosophy, of politics, of healing, of many things is very deep. However, it’s taken for granted, and they’re told that science is something else. Take Ayurveda; right now Ayurvedic physicians have a lot of respect. Even then, Ayurveda is treated as though it’s not science.

This touches a personal chord with me. As a child, my father had told me how he had been mercilessly teased for speaking Malayalam, his mother tongue, in an English medium school. He had harboured dreams of being an Ayurvedic doctor, but, as he recounted with quiet rage, his uncles literally whipped the idea out of his head, and forced him to become an allopathic doctor. Back then, and I realise even in my generation, the benchmark for success was to go abroad. A Quit India movement for Indians.

Anjali: There is such shame and hatred harboured towards our history. Why is that?

Raghu: As we’ve been discovering, our history, our perspective of ourselves comes from Western eyes that deem us savage and uncivilised. We also have an envy of the West. When you’re sitting on the other side of an envy of someone or something, you can only have self hate in various forms. Self hate is a horrible place to be in, and I don’t think that it would go away if you went abroad.

Anjali: You would continue to carry that feeling of inferiority.

Raghu: Somewhere inside of you, yes. Not that people haven’t done well in the West, and I know a lot of people who have. But I don’t know what happens to them, inside of themselves. How they resolve it, or don’t. I just know that it wouldn’t have worked for me to do that.

Anjali: You were saying earlier that you began to feel a sense of duty and responsibility…

Raghu: I wouldn’t say duty.

Anjali: Why not?

Raghu: You get exposed to all this, if you care to listen to a Seshadri or a Dharampal, if you care to just go out and experience it for yourself, like my Naxalite friend. He would talk about the reality of Andhra and Telangana; in fact after he joined the movement, he went off and he was killed later on.

One wasn’t just listening to his reality, you could go out into the villages, travel just a little bit, and you could see the reality he was talking about.

It’s not as though everything Indian is glorious. There’s been a lot of feudal misuse of power, caste misuse of power. It’s only when you go into the history, that you can understand what you see today is a decadent form of something that was contextually good and meaningful at another point in time. Feudalism is not something that was part of the Indian design. You begin to understand that when you study Dharampal, when you begin to study what was happening in the 1700s. But there is a very current reality of oppression in India.

It’s not as though everything Indian is glorious. There’s been a lot of feudal misuse of power, caste misuse of power. It’s only when you go into the history, that you can understand what you see today is a decadent form of something that was contextually good and meaningful at another point in time. Feudalism is not something that was part of the Indian design. You begin to understand that when you study Dharampal, when you begin to study what was happening in the 1700s. But there is a very current reality of oppression in India.

We had professors, like Professor Seshadri, who would sit and talk with us about the current reality, and he was a wonderful example of someone who at that time was using his expertise to solve Indian issues. So when you see all this, if you’re a sensitive person, you have to respond.

Anjali: So, there was no choice.

Raghu: Not for me.

Anjali: And once this had become clear to you, that there was really no choice, what did you do?

Raghu: First of all, I decided not to go abroad. When I finished IIT, I decided that I would work in India. And the next thing that happened to me was that I had a couple of professors from IIT sitting me down and advising me that there was something wrong with me.

The corner of Raghu’s mouth turns up as he recalls the incident.

“One of them pointed out that my uncle was a very big scientist, and I wouldn’t even have to look for a scholarship. Why was I not going abroad? I told him what I believed, that the idea of creating IIT (which is written in the charter) was to create people with technological capabilities to help India, his response was, “You don’t have to take it so seriously.” Raghu shrugs. “He was caught up with his idea that India is a terrible place. What else would he say?”

Anjali: So you finished IIT, with the decision to stay in India. What then?

Raghu: I joined my father in his business. That ended up being a very bad period actually, because he didn’t know how to run a business, and he ended up gathering a huge amount of losses. He didn’t just lose a lot of money, he lost his reputation, and the situation was quite damaging. I didn’t know about this when I joined him, so although I made a lot of changes in the way the operations were being done, there was nothing I could do about the financial reality. After a few years, the whole thing crashed. I inherited debts that took the next 10 years to repay, and there was a lot of underhanded dealings that had been done. I understood deeply how not to run a business. Which has been very useful, but at that time was extremely painful. It was an education.

Anoop is a student of Yoga, an entrepreneur, a coach and a father of two young boys. He has led successful leadership stints in both the corporate and non-for-profit sectors. On encountering the country’s water/farmer crises at close quarters, he decided to pause and examine the impact various ‘isms’ – capitalism, colonialism, etc., were having on us as individuals, families, the society and the environment at large. This quest led him to formally engage with traditional Indic knowledge systems while also learning from the latest advances in science – about our physical and mental wellbeing, importance of body and mind work in healing trauma and the urgent need for a conscious rebuilding of family / work / social structures if we have to thrive individually and collectively. Insights, frameworks and processes gleaned from these on-going studies, an anchorage in his own personal practice and his wide-ranging experiences is what Anoop brings to facilitation/coaching spaces in Ritambhara and his various professional engagements.

Anoop is a student of Yoga, an entrepreneur, a coach and a father of two young boys. He has led successful leadership stints in both the corporate and non-for-profit sectors. On encountering the country’s water/farmer crises at close quarters, he decided to pause and examine the impact various ‘isms’ – capitalism, colonialism, etc., were having on us as individuals, families, the society and the environment at large. This quest led him to formally engage with traditional Indic knowledge systems while also learning from the latest advances in science – about our physical and mental wellbeing, importance of body and mind work in healing trauma and the urgent need for a conscious rebuilding of family / work / social structures if we have to thrive individually and collectively. Insights, frameworks and processes gleaned from these on-going studies, an anchorage in his own personal practice and his wide-ranging experiences is what Anoop brings to facilitation/coaching spaces in Ritambhara and his various professional engagements.

Priya is a Yoga therapist in the Krishnamacharya tradition. She adapts Reiki & energy work, Vedic chanting, life coaching & Ayurvedic practices in her healing spaces. She is committed to nurturing collectives that have the praxis of Yoga at their heart.

Priya is a Yoga therapist in the Krishnamacharya tradition. She adapts Reiki & energy work, Vedic chanting, life coaching & Ayurvedic practices in her healing spaces. She is committed to nurturing collectives that have the praxis of Yoga at their heart. Anisha has been on an exploration to understand herself through yoga for the last 15years which led her to teaching yoga, yoga therapy and inner work through yoga.

Anisha has been on an exploration to understand herself through yoga for the last 15years which led her to teaching yoga, yoga therapy and inner work through yoga. Apoorva chanced upon Yoga in her early 20s. A spark was lit within and there was no turning back. Her exploration led her to the Krishnamacharya tradition more than a decade ago. Curious about human behaviour and what drives it, she was thrilled when her search ended (and also began) when she first came upon the Yoga Sutra, which illuminated a path towards answering many questions that had been held for a long time.

Apoorva chanced upon Yoga in her early 20s. A spark was lit within and there was no turning back. Her exploration led her to the Krishnamacharya tradition more than a decade ago. Curious about human behaviour and what drives it, she was thrilled when her search ended (and also began) when she first came upon the Yoga Sutra, which illuminated a path towards answering many questions that had been held for a long time. Anita is a yoga teacher and therapist in the tradition of Sri.T.Krishnamacarya and Sri T.K.V. Desikachar, a Reiki practitioner and a Life Coach. She is also the founder of Vishoka, a center for learning Indic and energy-based frameworks for living and healing. Her deep concern for human suffering and the problems of unsustainable living kept her on the path of seeking an integrated approach to looking at life, living, learning and healing.

Anita is a yoga teacher and therapist in the tradition of Sri.T.Krishnamacarya and Sri T.K.V. Desikachar, a Reiki practitioner and a Life Coach. She is also the founder of Vishoka, a center for learning Indic and energy-based frameworks for living and healing. Her deep concern for human suffering and the problems of unsustainable living kept her on the path of seeking an integrated approach to looking at life, living, learning and healing. Ankit is a seeker in the wisdom traditions of India. The core of his work includes creating dialogic spaces where people can look within and see the connection between their inner and outer lives. Inspired by the likes of Gandhi, Aurobindo, Vivekananda and Guru Gobind his experiments in service took him back to his roots in Punjab where he is creating a community-led model of higher education which is open, inclusive and accessible for all. Ritambhara for him is a space for engaging in a community which is committed to a DHramic life. He anchors his work of learning and leadership in the Antaranga Yoga Sadhana and the humanistic wisdom of Mahabharata.

Ankit is a seeker in the wisdom traditions of India. The core of his work includes creating dialogic spaces where people can look within and see the connection between their inner and outer lives. Inspired by the likes of Gandhi, Aurobindo, Vivekananda and Guru Gobind his experiments in service took him back to his roots in Punjab where he is creating a community-led model of higher education which is open, inclusive and accessible for all. Ritambhara for him is a space for engaging in a community which is committed to a DHramic life. He anchors his work of learning and leadership in the Antaranga Yoga Sadhana and the humanistic wisdom of Mahabharata.

This is wonderful insight! Will the next part also be posted sometime?