Leadership and management development seems to be taking a liking for ‘Mindfulness’. A lot of research is getting published, and most of it focuses on CEOs and how they benefit from 20 minutes of mindfulness practice. I am sure every organisation member will gain immensely from its practice.

One of the most delightful taxi rides I have ever had was one in which the taxi driver was calmness personified as he drove through particularly unruly traffic. He was a regular meditator. I remember commenting about his attitude, “You have to handle this every day for long hours” I said. A fascinating discussion ensued on how important it is for a person to go back home after a difficult day’s work in a state of mind where he can smile at his wife and play with his children. “Yoga and dhyāna are indispensable for me” was his final statement. He practised prāṇāyāma to prepare himself for the rigours of the day and also as soon as he finished his workday, he kept repeating a japa whenever we stopped at traffic lights!

I am delighted that an ancient Indian practice is getting the attention it deserves. I do not doubt that all the research done by Jon Kabat-Zinn and other leading researchers on the Buddhist meditators from Dalai Lama’s senior monks is excellent work. However, a few tendencies worry me.

Mindfulness- the ‘active ingredient’

Firstly, there is a presentation of ‘mindfulness’ as if it is ‘the active ingredient’ of deep spiritual practice. This is reminiscent of Pharmaceutical companies that study many traditional practices and medicines and analyze the healing herbs to extract the one chemical that is the essential curative element. This chemical is then patented, and synthesized in a factory, the future now belongs to that company’s top line! When we look at ‘dhyāna’ or ‘ānapānasati’ the original practices, we find that they are part of a holistic set of practices and worldviews. ‘Mindfulness’ is starting to sound like a pill that has been distilled out of the original messy mix.

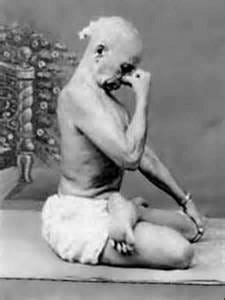

Dhyāna is embedded in Yogic discipline

Let me illustrate: dhyāna is one of the ‘eight limbs’ of Yogic discipline. All Indian Spiritual teachings accept these eight limbs or suggest variations of the discipline. For example, the worldview that characterizes both Yogic and Buddhist thought, makes attentiveness, contemplation and meditation a central practice of a life that is directed towards spiritual attainment. Householders, Kings, Monks and people from all walks of life who valued the spiritual path practised a form of meditation that was meaningful to them. Dhyāna is not a ‘detachable fragment’! The practice of ahiṃsā is an essential prerequisite and dhārmik living is the goal. It has been recognized that when the ‘active agents’ are separated from the holistic herbal preparations there are ‘side effects’ that the whole herb does not create. Often the herb is part of a dietary regimen and an integral part of a holistic treatment. One wonders what the side effects would be of practising ‘mindfulness the pill’.

Dhyāna is essential for sustainable living

Secondly, the contemplative practices have grown out of the worldview that a human being is “part of Nature”. What happens when this idea is plucked out of its nutrient medium and placed, often sold, as a tool for effectiveness? IMHO, dhyāna is a practice that ought to lead to the development of ecologically sensitive and ‘sustainable’ ways of deploying science and technology. Mindfulness, as it is promoted, will probably enhance the effectiveness of executives who do not wish to ask difficult questions regarding their motivations, the impact of their business on the environment, on equity and the like. This is because these practices that make one’s mind sharper and more retentive are placed in a context that values ‘utilitarianism’ as its defining characteristic.

Cultural Appropriation

Thirdly, ‘Mindfulness’ is presented as if it is a Western discovery. If one reads Wikipedia (popularly seen as the arbiter of truth!) one comes across this line: “a famous exercise, introduced by Kabat-Zinn in his MBSR-program, is the mindful tasting of a raisin, in which a raisin is being tasted and eaten mindfully”, now this was something that Thich Nhat Hanh has often written about. The psychological correlates of mindful eating and savouring the ‘six rasa’ is part of Ayurvedic lore. Many such simple practices set in the everyday mundane routines of living are recommended dhāraṇā (contemplative) practices that my teacher Yogacharya Krishnamacharya would mention casually.

I am sure the serious researchers are not part of this ‘cultural appropriation’. But like most of ‘yoga’ has been plucked out of its context and innovated out of recognition in the process of making it accessible (more commercially viable?), we run the risk of a practice that has profound possibilities becoming a “pill for an ill”.

Dhyāna and higher purpose

Dhyāna practices seriously and in the traditional way will lead to the discovery of the higher purpose of one’s life. This “higher purpose” cannot be the answer to questions like “How do I make more profits?” nor “How do I get the next promotion?” The common discourse is now peppered with references to the “Poly crisis” as the World Economic Forum calls the Anthropocene. This points to an urgent, perhaps long-overdue need to fundamentally reorient the use of science and technology in the service of world peace, sustainability and equity. Dhyāna’ and ‘ānapānasati’ are set in a philosophy that places great emphasis on compassion. I am not sure ‘mindfulness’ cares about this philosophy; it is most commonly presented in the context of personal success.

Anoop is a student of Yoga, an entrepreneur, a coach and a father of two young boys. He has led successful leadership stints in both the corporate and non-for-profit sectors. On encountering the country’s water/farmer crises at close quarters, he decided to pause and examine the impact various ‘isms’ – capitalism, colonialism, etc., were having on us as individuals, families, the society and the environment at large. This quest led him to formally engage with traditional Indic knowledge systems while also learning from the latest advances in science – about our physical and mental wellbeing, importance of body and mind work in healing trauma and the urgent need for a conscious rebuilding of family / work / social structures if we have to thrive individually and collectively. Insights, frameworks and processes gleaned from these on-going studies, an anchorage in his own personal practice and his wide-ranging experiences is what Anoop brings to facilitation/coaching spaces in Ritambhara and his various professional engagements.

Anoop is a student of Yoga, an entrepreneur, a coach and a father of two young boys. He has led successful leadership stints in both the corporate and non-for-profit sectors. On encountering the country’s water/farmer crises at close quarters, he decided to pause and examine the impact various ‘isms’ – capitalism, colonialism, etc., were having on us as individuals, families, the society and the environment at large. This quest led him to formally engage with traditional Indic knowledge systems while also learning from the latest advances in science – about our physical and mental wellbeing, importance of body and mind work in healing trauma and the urgent need for a conscious rebuilding of family / work / social structures if we have to thrive individually and collectively. Insights, frameworks and processes gleaned from these on-going studies, an anchorage in his own personal practice and his wide-ranging experiences is what Anoop brings to facilitation/coaching spaces in Ritambhara and his various professional engagements.

Priya is a Yoga therapist in the Krishnamacharya tradition. She adapts Reiki & energy work, Vedic chanting, life coaching & Ayurvedic practices in her healing spaces. She is committed to nurturing collectives that have the praxis of Yoga at their heart.

Priya is a Yoga therapist in the Krishnamacharya tradition. She adapts Reiki & energy work, Vedic chanting, life coaching & Ayurvedic practices in her healing spaces. She is committed to nurturing collectives that have the praxis of Yoga at their heart. Anisha has been on an exploration to understand herself through yoga for the last 15years which led her to teaching yoga, yoga therapy and inner work through yoga.

Anisha has been on an exploration to understand herself through yoga for the last 15years which led her to teaching yoga, yoga therapy and inner work through yoga. Apoorva chanced upon Yoga in her early 20s. A spark was lit within and there was no turning back. Her exploration led her to the Krishnamacharya tradition more than a decade ago. Curious about human behaviour and what drives it, she was thrilled when her search ended (and also began) when she first came upon the Yoga Sutra, which illuminated a path towards answering many questions that had been held for a long time.

Apoorva chanced upon Yoga in her early 20s. A spark was lit within and there was no turning back. Her exploration led her to the Krishnamacharya tradition more than a decade ago. Curious about human behaviour and what drives it, she was thrilled when her search ended (and also began) when she first came upon the Yoga Sutra, which illuminated a path towards answering many questions that had been held for a long time. Anita is a yoga teacher and therapist in the tradition of Sri.T.Krishnamacarya and Sri T.K.V. Desikachar, a Reiki practitioner and a Life Coach. She is also the founder of Vishoka, a center for learning Indic and energy-based frameworks for living and healing. Her deep concern for human suffering and the problems of unsustainable living kept her on the path of seeking an integrated approach to looking at life, living, learning and healing.

Anita is a yoga teacher and therapist in the tradition of Sri.T.Krishnamacarya and Sri T.K.V. Desikachar, a Reiki practitioner and a Life Coach. She is also the founder of Vishoka, a center for learning Indic and energy-based frameworks for living and healing. Her deep concern for human suffering and the problems of unsustainable living kept her on the path of seeking an integrated approach to looking at life, living, learning and healing. Ankit is a seeker in the wisdom traditions of India. The core of his work includes creating dialogic spaces where people can look within and see the connection between their inner and outer lives. Inspired by the likes of Gandhi, Aurobindo, Vivekananda and Guru Gobind his experiments in service took him back to his roots in Punjab where he is creating a community-led model of higher education which is open, inclusive and accessible for all. Ritambhara for him is a space for engaging in a community which is committed to a DHramic life. He anchors his work of learning and leadership in the Antaranga Yoga Sadhana and the humanistic wisdom of Mahabharata.

Ankit is a seeker in the wisdom traditions of India. The core of his work includes creating dialogic spaces where people can look within and see the connection between their inner and outer lives. Inspired by the likes of Gandhi, Aurobindo, Vivekananda and Guru Gobind his experiments in service took him back to his roots in Punjab where he is creating a community-led model of higher education which is open, inclusive and accessible for all. Ritambhara for him is a space for engaging in a community which is committed to a DHramic life. He anchors his work of learning and leadership in the Antaranga Yoga Sadhana and the humanistic wisdom of Mahabharata.