Ambujam Venkatraman & Raghu Ananthanarayanan

Just the other day, Mother visited us. I was fascinated to listen to her travel back in time recollecting memories of an era gone by. Her story is not uncommon — It is the story of many people who recall the days before independence and the times after that. It is poignant and sad. At one level, it is a narrative of formative changes, and at another, a tale of hopes belied; of the effects of colonisation and the arduous process of reclaiming. She often said, “In those days, our strength lay hidden beneath layers of oppression, but it was always there, waiting to be rediscovered”.

My mother, Ambujam Venkatraman, is well known to those who read books on Indian Income tax. A. Venkatraman was the name used by the publishing family business cleverly disguising the gender, conceding to a fact that the male-dominated field of Income tax lawyers and auditors would not accept a female author!

Listen to her voice:

Today, I am 92 years old. As far back as I can remember, I can only feel strong emotions. Emotions that aroused in me fear and anxiety. My early childhood memories are clouded with events and episodes that one would characterise as an atmosphere of fear and oppression.

Fear is Induced

I vividly recall the stark image of railway carriages reserved exclusively for the British. These carriages were meticulously maintained, gleaming with fresh paint, and adorned with elegant insignia that marked them off-limits to us. The air around them seemed to hum with an unspoken declaration of superiority. Even as a small child, I could sense the invisible barrier that separated us from them.

The sight of a British child emerging from one of these carriages is seared into my memory. The child, no older than me, would step out with a swagger, a casual arrogance that seemed innate. The mere presence of this child was enough to send a ripple of fear through the adults around me. I remember how they would avert their eyes, their postures suddenly shrinking as if trying to make themselves invisible. It was a fear I didn’t fully understand then, but I could feel its weight pressing down on us.

The sounds of that time were equally telling. The rhythmic clatter of the train wheels on the tracks, a sound that should have been comforting in its regularity, instead felt like a constant reminder of our subjugation. The occasional sharp whistle of the train pierced the air, a symbol of authority and control. And then there were the hushed voices of my elders, their whispers carrying a mix of resentment and resignation, always mindful of being overheard. The smells, too, were part of this oppressive atmosphere. The scent of coal smoke from the engines mingled with the sharp tang of metal and the faint, lingering aroma of the aromatic oils the British favoured. These scents combined to form a sensory tapestry that spoke volumes about our divide.

The Emotional Cauldron

Growing up under the shadow of British rule, my preteen years were marked by a tumultuous blend of emotions. My mind was a cauldron, bubbling with confusion, anger, and a burgeoning sense of injustice. I was acutely aware that the British were our rulers, and their disdain for us was palpable in every aspect of daily life. This contempt extended to our Bhāratīya culture, which they criticised with biting cruelty.

The sting of their criticism cut deep. They dismissed our religion as primitive, their voices dripping with condescension as they ridiculed the sacred scriptures that had been passed down through generations. They claimed that our texts revealed a grotesque misunderstanding of human anatomy, mocking the profound wisdom contained within them. Hearing such disparagement of something integral to our identity was deeply hurtful. Their disdain did not stop at religion.

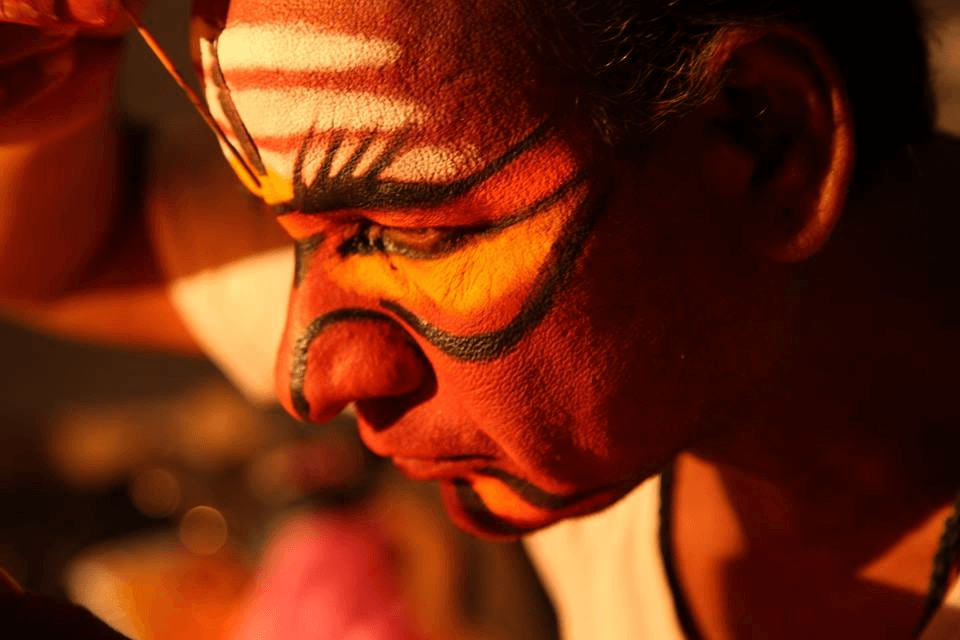

The British dismissed our classical music, a source of immense pride and spiritual expression, as mere cacophony. The intricate rhythms and melodies that resonated with our souls were reduced to noise in their ears. It was as if they were deaf to the beauty within the complexities of our ragas and talas. Each note and beat was a testament to our rich cultural heritage, yet it was all lost on them.

Similarly, our dance forms, which encapsulated the stories and emotions of our people, were reduced to a series of ugly jumps and poses. The grace and profound expression in Bharatanatyam, Kathak, and other classical dances were invisible to the British. They saw only awkward movements and dismissed the profoundly symbolic and aesthetic elements woven into every performance.

This pervasive criticism was not just hurtful; it instilled a sense of inferiority. The British mind was often portrayed as far superior in science and industry, and it was suggested that a Bhāratīya could not even begin to comprehend their advancements. This intellectual and cultural superiority narrative was reinforced in schools, the media, and casual conversations. It created a deep-seated belief among us that we were inherently inferior.

I remember feeling a profound sense of conflict during those years. On the one hand, there was outrage at the unjust criticism and a fierce pride in our heritage. On the other hand, there was a gnawing doubt, a fear that perhaps the British were right about their superiority. This internal struggle was intensified by the lack of resources to counter their claims. At that time, I had yet to encounter the works of great thinkers and leaders who would later provide the validation I craved.

Pride is Kindled

Amid this turmoil, the stories and teachings my elders passed down to me became lifelines. They reminded me of the depth and richness of our culture, the wisdom in our scriptures, and the beauty of our arts. These teachings helped me hold on to a sense of pride and counterbalance the pervasive narrative of inferiority.

Looking back, those years were crucial in shaping my identity. The criticism and contempt we faced fuelled my determination to seek out and understand the actual value of our culture. This quest eventually led me to Swami Vivekananda’s works and the Upanishads’ profound wisdom, which solidified my faith and pride in our Bharatiya heritage.

However, I continued to believe that our civilisation needed to catch up in science, math, and applied sciences for a long time. Intuitively, I felt that this was not true. Independence brought euphoria, but soon, I was disappointed because no effort was made to study our literature and contributions to every field.

I now know enough to recognise the greatness of our temples, which showed a mastery of architecture and sculpture, the excellent work of Kalidasa. I had believed naively that there would be a great effort in learning and propagating this knowledge. In the 1960s, I read Naipaul’s book A Million Mutinies in India.

I understood that the desire to learn about our civilisation was widespread. Naipaul travelled the length and breadth of India, even among the so-called uneducated and poor people. There was this deep angst.

I felt very helpless. It was in the late 60s, and thanks to my son, who was then studying at IIT Madras and who had come under the influence of Shri Dharampal, a ray of hope dawned amidst the gloom. I avidly read all of Shri Dharampal’s books.

This was a moment of great joy to me. There was solid proof that what I had gathered by my haphazard reading and what I felt deeply in and intuitively were all true. The other thing that saddened me deeply was that after independence, there was no grand celebration of the INA and Subhash Chandra Bose.

I remember with incredible thrill the tremendous excitement we all felt when Captain Lakshmi and others from INA toured the country. All Indians of all ages followed the trial of the INA officers and Bullabhai Desai’s defence of them. In the narrative about Indian independence, these people were not mentioned at all.

Post Independence Let-down

All of us knew that there was no mention of these people at all who were, as we knew, as instrumental as Gandhiji and Pandit Nehru in getting freedom. All of us knew about the torture undergone by Veer Savarkar and many others in the notorious prisons in the Andamans.

There were heroes like Bhagat Singh, Vanchinathan, and Chandrasekhar Azad who suffered and sacrificed their lives for the motherland. The list could go on and on. Mention should also be made of people like V.O. Chidambaram Pillai, the Birlas, and the Tatas, who started industries and defied the British.

When the British left, they adopted a scorched earth policy. There was an arbitrary partition and an announcement that with their dependence, paramountcy would revert to the native rulers, who numbered more than 500. The British were sure that there would be chaos with the numerous small kingdoms on the one hand and the confusion resulting from an ill-determined partition on the other. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel ensured all the rulers acceded to India and prevented a complete breakup of India. He was called the Iron Man, and even his name did not figure predominantly in the story of Indian independence.

Hope Returns

The truth could not be suppressed forever. Scholars appeared. P. Sambamurthy wrote treatises on Carnatic classical music. There were translations of treatises on dance and drama. Institutions like Ramakrishna Mission and later Chinmaya Mission published easy-to-read and inexpensive books in English and other Indian languages dealing with spirituality, ethics, art and culture. There were books on Aryabhata and Bhaskara. Things took longer in the political arena. Seeing many people talking about our ancient civilisation and the colonisation of minds is heartening.

During the pandemic, I was forced to start using YouTube. These days, I listen to Sri Malhotra, Professor Raj Vedam, and Professor Nilesh Oak, amongst others. Books by Sanjeev Sanyal, Meenakshi Jain, Sai Deepak, and Vikram Sampath are very lucid and full of factual details that help one understand one’s own past. In the last years of my life, I am incredibly grateful to all these scholars who have enabled me to look forward to the future optimistically.

Anoop is a student of Yoga, an entrepreneur, a coach and a father of two young boys. He has led successful leadership stints in both the corporate and non-for-profit sectors. On encountering the country’s water/farmer crises at close quarters, he decided to pause and examine the impact various ‘isms’ – capitalism, colonialism, etc., were having on us as individuals, families, the society and the environment at large. This quest led him to formally engage with traditional Indic knowledge systems while also learning from the latest advances in science – about our physical and mental wellbeing, importance of body and mind work in healing trauma and the urgent need for a conscious rebuilding of family / work / social structures if we have to thrive individually and collectively. Insights, frameworks and processes gleaned from these on-going studies, an anchorage in his own personal practice and his wide-ranging experiences is what Anoop brings to facilitation/coaching spaces in Ritambhara and his various professional engagements.

Anoop is a student of Yoga, an entrepreneur, a coach and a father of two young boys. He has led successful leadership stints in both the corporate and non-for-profit sectors. On encountering the country’s water/farmer crises at close quarters, he decided to pause and examine the impact various ‘isms’ – capitalism, colonialism, etc., were having on us as individuals, families, the society and the environment at large. This quest led him to formally engage with traditional Indic knowledge systems while also learning from the latest advances in science – about our physical and mental wellbeing, importance of body and mind work in healing trauma and the urgent need for a conscious rebuilding of family / work / social structures if we have to thrive individually and collectively. Insights, frameworks and processes gleaned from these on-going studies, an anchorage in his own personal practice and his wide-ranging experiences is what Anoop brings to facilitation/coaching spaces in Ritambhara and his various professional engagements.

Priya is a Yoga therapist in the Krishnamacharya tradition. She adapts Reiki & energy work, Vedic chanting, life coaching & Ayurvedic practices in her healing spaces. She is committed to nurturing collectives that have the praxis of Yoga at their heart.

Priya is a Yoga therapist in the Krishnamacharya tradition. She adapts Reiki & energy work, Vedic chanting, life coaching & Ayurvedic practices in her healing spaces. She is committed to nurturing collectives that have the praxis of Yoga at their heart. Anisha has been on an exploration to understand herself through yoga for the last 15years which led her to teaching yoga, yoga therapy and inner work through yoga.

Anisha has been on an exploration to understand herself through yoga for the last 15years which led her to teaching yoga, yoga therapy and inner work through yoga. Apoorva chanced upon Yoga in her early 20s. A spark was lit within and there was no turning back. Her exploration led her to the Krishnamacharya tradition more than a decade ago. Curious about human behaviour and what drives it, she was thrilled when her search ended (and also began) when she first came upon the Yoga Sutra, which illuminated a path towards answering many questions that had been held for a long time.

Apoorva chanced upon Yoga in her early 20s. A spark was lit within and there was no turning back. Her exploration led her to the Krishnamacharya tradition more than a decade ago. Curious about human behaviour and what drives it, she was thrilled when her search ended (and also began) when she first came upon the Yoga Sutra, which illuminated a path towards answering many questions that had been held for a long time. Anita is a yoga teacher and therapist in the tradition of Sri.T.Krishnamacarya and Sri T.K.V. Desikachar, a Reiki practitioner and a Life Coach. She is also the founder of Vishoka, a center for learning Indic and energy-based frameworks for living and healing. Her deep concern for human suffering and the problems of unsustainable living kept her on the path of seeking an integrated approach to looking at life, living, learning and healing.

Anita is a yoga teacher and therapist in the tradition of Sri.T.Krishnamacarya and Sri T.K.V. Desikachar, a Reiki practitioner and a Life Coach. She is also the founder of Vishoka, a center for learning Indic and energy-based frameworks for living and healing. Her deep concern for human suffering and the problems of unsustainable living kept her on the path of seeking an integrated approach to looking at life, living, learning and healing. Ankit is a seeker in the wisdom traditions of India. The core of his work includes creating dialogic spaces where people can look within and see the connection between their inner and outer lives. Inspired by the likes of Gandhi, Aurobindo, Vivekananda and Guru Gobind his experiments in service took him back to his roots in Punjab where he is creating a community-led model of higher education which is open, inclusive and accessible for all. Ritambhara for him is a space for engaging in a community which is committed to a DHramic life. He anchors his work of learning and leadership in the Antaranga Yoga Sadhana and the humanistic wisdom of Mahabharata.

Ankit is a seeker in the wisdom traditions of India. The core of his work includes creating dialogic spaces where people can look within and see the connection between their inner and outer lives. Inspired by the likes of Gandhi, Aurobindo, Vivekananda and Guru Gobind his experiments in service took him back to his roots in Punjab where he is creating a community-led model of higher education which is open, inclusive and accessible for all. Ritambhara for him is a space for engaging in a community which is committed to a DHramic life. He anchors his work of learning and leadership in the Antaranga Yoga Sadhana and the humanistic wisdom of Mahabharata.